by Mark Anderson

I’m a big fan of puzzles. Crossword puzzles, brainteasers, jigsaw puzzles. Without a doubt, my favorite part of project climbing is solving the sequence puzzle. The more baffling the sequence, the more rewarding it is to solve. This challenge is magnified on first ascents, which typically lack obvious clues like chalk and rubber marks. Furthermore, there’s no guarantee a new line will provide a free solution. For me, there’s nothing quite like the Eureka Moment when I finally convince myself the route will indeed go free. It could be the first time I execute a particularly cruxy move, the first time I complete a certain link through the crux, or even the first one-hang. In any case, that realization is followed by a renewed belief that the project is viable.

But there’s a downside to the Eureka Moment. It’s only a small leap from there to assuming the redpoint is all but assured—a mere formality. That assumption is often wrong, and the mindset it yields is counter-productive at best. If the send doesn’t follow promptly, each ensuing attempt is weighed down by a few more ounces of anxiety. Thoughts about the next objective creep in, I wonder how many more times I will need to line up a partner, and if the days turn into weeks, concerns about when to start my next training cycle add a bit more weight. This ballast is indiscernible at first, but over time, it adds up. This is purgatory—the prime malady of the projecting process.

To be in sport climbing purgatory is to know unlimited misery. It’s like being locked in a cage, with everything you desire just out of reach of your extended arm. Each morning you walk to the crag, passing other routes you might climb, if only you could send your project. Each afternoon, you walk back, trying to reason your way into believing you’ll send it the next day, but knowing deep down that you probably won’t.

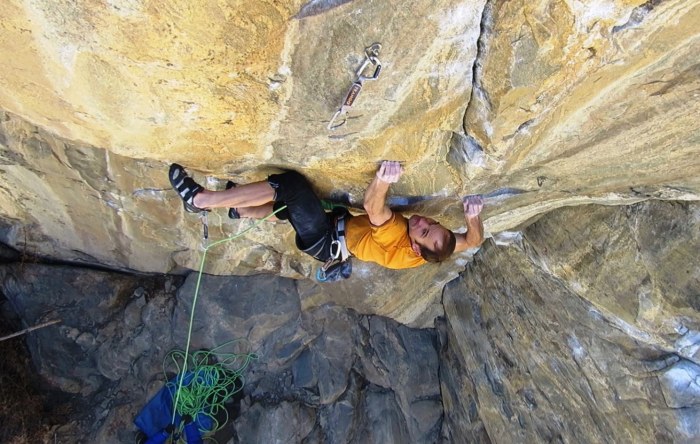

Purgatory looks something like this. Bystanders will say it looks beautiful. From the inside looking out, all you see is pain.

The past 40 days have been the longest continuous purgatory of my career. After finishing Double Stout, I was eager to try another long-standing open project in Clear Creek Canyon. This one was prepped by my friend Scott Hahn around 2008, and opened to all comers in the spring of 2009. It’s located at The Armory, a small crag with an unusual concentration of great routes, including Ken T’ank, The Gauntlet, and Beretta. The Gauntlet was established in 2006 by Darren Mabe at 5.12+. It starts up a leaning dihedral, and then moves left onto a steep face of impeccable orange stone to climb a splitter finger crack capped off by a challenging roof encounter. Scott’s line was essentially a direct start to The Gauntlet, avoiding the dihedral by climbing straight up to the finger crack.

The direct start is all business from the moment you step off the ground until you reach a pair of bomber fingerlocks at mid-height. Scott described the difficulties reaching the crack as “roughly V10 into V12”, with the caveat that “a good wingspan is a must or you won’t be able to reach the holds”.

My first day on the route I was completely perplexed. There were many holds, but I couldn’t surmise how to use them. It’s one of those routes with such non-positive holds that just pulling onto the rock, while hanging from the rope, is quite difficult. There are many sidepulls, underclings, and slopers, and I could see the key was going to be figuring out the right combination of opposing holds and body position to stay on the rock. It would take time to learn how to move between those positions, and momentum to execute those moves.

For two more days I attempted to solve the puzzle, but there were still moves I couldn’t do, particularly in the reachy “V10” entry problem. There was an obvious “tall guy” sequence for this lower section, but I needed to come up with an alternative. I had done all the moves in the upper “V12” section, but it was much longer, very sustained, and I was far from linking the entire sequence. On the fourth day I finally uncovered a Napoleonic path through the first problem, and I managed to do the V12 bit in two sections with a hang. Now I knew the route would go. Great news, right?

The month of February is a blur of steady progress, devolving into near misses, clouded by a haze of fickle weather forecasts. The route started to come together in mid-February. I got my first one-hang, and then it seemed I was climbing up to the last one or two hard moves on redpoint more often than not.

Then the entire country was engulfed in historically heinous winter weather caused by an extremely cold air mass referred to by meteorologists as the “Siberian Express”. Record cold temps infiltrated the Eastern Seaboard—typically mild places like Tennessee and Kentucky were ice-bound, and Niagara Falls froze long enough to enable Will Gadd’s stunning ascent. In Colorado, the phenomenon manifested itself as massive amounts of snow. During the last two weeks of February alone Denver received enough snowfall to shatter the record for the entire month.

Through the bars of purgatory, it seemed like it snowed every day. I like cold weather for hard climbing, and normally I can operate in the 20’s if it’s calm, but in late February The Armory rarely experienced temps above the teens. I managed to find one day each week in which the weather was barely tolerable for climbing. It wasn’t warm enough to send, but it allowed me to keep the moves fresh in my mind, and keep the candle of hope flickering ever so dimly.

Typically when a project gets out of hand I retreat, re-train, and return in a following season, usually completing the project with relative ease the next time around. I didn’t want to do that this time. For one reason, I felt extremely close to sending—much closer than I normally am when I bail. For another, I was concerned that the unpredictable Front Range weather would not provide another window of solid redpoint conditions until next winter. This is the sort of route you want to climb when it’s cold (well, to a point), and it would be difficult to get back to the route with good fitness before excessively warm weather arrived in Clear Creek. Finally, I had started to worry that my “retreat, re-train and return” strategy was becoming a crutch. I wanted to know if I had the mental fortitude to see this one through in a single campaign.

Fitness-wise, I was in danger of falling badly out of shape. I completed my last hangboard workout of the season on December 31st. With climbing in the V12-range, this project was right at my power limit, so I needed to maintain a power peak for as long as possible. Normally a nice long power peak lasts 3-4 weeks. To make it to the far end of the Siberian Express I would need to sustain my power for at least 8 weeks. Fortunately I could see early in the process that this project would take some time, so starting in late January I made a point to dedicate at least one session each week (and two per week during the worst weather) to sustaining my power and building power endurance through the use of Non Linear Periodization (NLP). As detailed in the RCTM, these sessions consisted of:

- Warmup Boulder Ladder (20 minutes)

- Limit Bouldering (25 minutes)

- [5-10 minute break]

- Campusing (Basic Ladders for warmup, then Max Ladders, 20-30 min total)

- [5-10 minute break]

- 4 sets of 34-move Linked Bouldering Circuit (Duty Cycle progressing from 1:1 to 2:1)

- [10 minute break]

- Supplemental Exercises (2 sets each of shoulder & core exercises)

This strategy worked astonishingly well. On February 15, I did 1-4.5-8 on the Campus Board for the first time (which seems to be slightly harder for me than 1-5-8, which I had done once before). On February 27th, the first day of my 9th week of power training, I did 1-5-8 and touched 1-5-8.5. I also completed my LBC with a duty cycle of 2.3 to 1 (1:45 set length with 45 seconds of rest between sets). I was strong and fit. I just needed some decent weather.

March arrived towing with it the first hint that snowpocalypse was waning. The first full weekend would bring highs in the 40’s and 50’s. By now I had everything dialed. The sub-optimal weather had forced me to fine tune every move, so I could stay on the sloping holds even when friction was poor. My warmup felt klunky and strenuous—usually a good sign. Once prepared for my first attempt of the day, I wandered down the hill to look at the river. The Armory is one of my favorite Clear Creek crags. It’s located across the river from a tunnel that mercifully muffles most of the road noise. There are a handful of massive pine trees that provide a beautiful backdrop, and the crag is sparse enough to escape the crowds of the nearby Primo Wall.

It was time to start. By now the entry problem, which took four days to unlock, was trivial. I flowed effortlessly up to the direct start’s one pseudo-jug. I quickly clipped the second bolt, chalked my right hand, and continued. From this point each of the next 12 or so hand moves is a dyno. I had fallen on redpoint on virtually all of these moves at one point or another, and not necessarily in progressive fashion. The climbing is so insecure and complex that the actions of each limb must be carefully coordinated. If your attention wanders for even a split second you can pop off at literally any point.

This time I made no mistakes. I performed each move in exacting fashion, and I flowed from one into the next. Breathing heavily, I lined up for the final slap, this one to a sharp horizontal water groove on the edge of a protruding horn—the last hard move. I had fallen on this move on redpoint seven times, but I had never arrived at this move feeling as strong and confident as I did then. I lined up the hold, colied and slapped. By the time I realized what I had done I was sinking my second hand into the bomber finger crack. I clipped and exhaled. The final 30 feet were a sweet victory lap, and I was released from my self-made prison.

The effort was a revelation for me. I’ve never maintained peak fitness for so long. All my knowledge of training, strategy and tactics contributed. I’ve never stubbornly persisted on a route for so long in a single season. I doubted the virtue of that persistence each day, and even knowing the outcome I’m not entirely convinced it was prudent, but it’s empowering to know I can fall back on that option in the future.

I’m calling the route Siberian Express. Based on my maintenance training I can confidently say that I was in top shape when I did it. The weather likely extended the outcome somewhat, but considering my fitness and the twelve days required, I suspect it’s the hardest route I’ve climbed and warrants a 5.14c rating. More importantly, it’s a great route. It doesn’t have the towering height of the lines on the Wall of the 90’s, but where it’s hard, it is incredibly sustained. It certainly doesn’t climb like a short route or a roped boulder problem. With few exceptions the rock is impeccable–truly some of the best in Clear Creek. The setting is serene, and the movement is fantastic, once you figure it out.

Nice work Mark!

LikeLike

Awesome job Mark, way to stick it out! It’s amazing what our bodies can do if we create the right stimuli!

LikeLike

good job on sending this long standing project! Your training adjustment to a NLP “phase” is a departure from how you have typically approached projects in the past: either send during performance phase or come back when conditions and future periodization cycles are aligned. Will you adopt this NLP approach in the future, meaning do you see potential advantages in overall performance (you seem to allude to as much with your campus results), never mind the convenience of not have to wait into an unknown future to send? And do you send any downsides to NLP?

LikeLike

Congratulations, Mark. Would you be willing to share your training calendar so we can see how and when you transitioned from the standard training cycle to the NLP cycle? For example, did you do a relatively “normal” power phase and then move into the NLP cycle, or did you start NLP during your power phase, etc.?

Thanks for anything you could share, as I think this is a common situation a lot of us find ourselves in.

LikeLike

I am also curious about the potential downsides to NLP. I would guess you wouldn’t want to get sucked into for too long because it would initially prevent a solid period of rest and eventually inhibit more dramatic gains that could be made in a more focused phase.

LikeLike

Pingback: Possible 5.14c FA By Mark Anderson | Climbing Narcissist

Hi,

Congrats! Always inspiring!

I’m also interested in your NLP approach. I was looking in the book for details on the training sessions you describe in this post but I didn’t find anything similar. Could you please tell me in which page you detail this?

LikeLike

Hey all,

For more info on my NLP approach, check out these threads in the RCTM Forum:

http://rockprodigytraining.proboards.com/thread/542/power-strength-hybrid-workout-maintenance

http://rockprodigytraining.proboards.com/thread/532/periodization-training-skipping-performance-phase

http://rockprodigytraining.proboards.com/thread/339/skip-performance-phase-winter-season

http://rockprodigytraining.proboards.com/thread/472/new-blog-post-rctm-com

If you have any more questions, please post them in a thread on the forum, which I check and respond to daily.

Thanks,

Mark

LikeLike

Greetings! I’ve been reading your site for some time now and finally got the

courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from Dallas Texas!

Just wanted to say keep up the excellent job!

LikeLike

Thanks Cortney! No courage needed, we are just two regular Joes 🙂

LikeLike

Hey Mark! It looks like you’re skipping the Hard Bouldering in your NLP Routine. Is this the case, or are you just grouping it in with your WBL / Limit Bouldering?

LikeLike

Yes, but it really depends on time. With 45 minutes of total bouldering, perhaps 15-20 minutes of that is WBL, and the rest could be Hard Boulder, Limit Bouldering, or a combination depending on what I’m interested in.

LikeLike

Pingback: Training for 9a – Part III | The Rock Climber's Training Manual

Pingback: Mark Anderson - Extending a Performance Peak - Training for Rock Climbing - TrainingBeta

Pingback: Extend Your Performance Peak with a Micro-Cycle | The Rock Climber's Training Manual

Pingback: How to Become an Expert Climber in Five Simple Lessons (Lesson 4) | The Rock Climber's Training Manual

This is a great post thankks

LikeLike